How to survive a nuclear attack comes down to speed, shielding, and smart choices. You do not need special gear to improve your odds. You need the right actions at the right time. The biggest danger for most people is not the blast itself. It is fallout in the hours and days after. Fallout can enter your lungs, land on skin, and contaminate food and water.

Your goal is simple: get inside fast, put dense material between you and the outside, remove contamination, and stay sheltered until radiation drops.

This guide explains what to do if you see a flash, hear warnings, or learn an attack happened nearby. It covers the first 60 seconds, the first hour, the first day, and the first week.

You will learn shelter choices, safe movement rules, decontamination steps, and what supplies matter most. You will also see checklists, tables, and quick decision rules. Read it once now. If an emergency happens, you will act faster and make fewer mistakes.

Know the Three Phases: Blast, Fallout, and Recovery

To understand a nuclear attack, split the event into phases. Phase one is the blast and heat. It can shatter windows, throw debris, and cause fires. If you are close, it can be fatal. If you are farther away, flying glass and collapse can still injure you. Phase two is fallout. Fallout is dust and debris that becomes radioactive.

It can start falling in 10–30 minutes near the target, or later farther away. Fallout radiation is strongest early and drops quickly over time. Phase three is the recovery period. You may face power loss, blocked roads, limited medical care, and communication problems.

This matters because each phase needs different actions. For blast risk, you need distance from windows and structural shelter. For fallout, you need time indoors and thick shielding. For recovery, you need clean water, safe food, and calm planning. Many people make one key mistake. They try to “escape” too soon. That can put them into heavy fallout outdoors. Staying put in a good shelter often saves more lives than driving.

Think in priorities: Get inside → Get deep → Stay put → Stay informed. If you memorize that chain, you can act under stress.

First 60 Seconds: What to Do If You See a Flash or Hear a Warning

If you want to know how to survive a nuclear attack, the first minute matters. If you see a bright flash, do not stare at it. Turn away at once. Drop behind a solid object. Cover your face and exposed skin. If you can, get behind a wall, curb, or concrete barrier. Heat and blast waves arrive after the flash, often within seconds to tens of seconds depending on distance. Your goal is to avoid burns and debris.

If you are indoors, get away from windows fast. Move to an interior room, hallway, or stairwell. Get low. Put a wall between you and the outside. If you are in a vehicle, pull over safely. Get out and get inside the nearest solid building if possible. Cars do not shield well from radiation or flying debris.

Avoid elevators. They can stop during outages. Use stairs. Do not run toward the blast to “see what happened.” Glass and debris will injure people who stand near windows. After the blast wave passes, you still must act quickly. Fallout may arrive soon. That means: get inside a solid structure, then move deeper into it.

Choose the Best Shelter Fast: The “Inside, Below, Center” Rule

A strong shelter is the core of how to survive a nuclear attack. Your best shelter reduces radiation exposure. Radiation weakens when you put dense material between you and fallout. It also weakens with distance and time. Use the “Inside, Below, Center” rule:

- Inside: Get into a building. Avoid staying outdoors.

- Below: Basements and underground levels work best.

- Center: Move to the middle floors or interior rooms away from outside walls and roof.

Concrete, brick, and earth block radiation better than wood or thin metal. A multi-story concrete building can be excellent if you go to an interior floor, away from roof and outer walls. A basement in a house can also work well, especially if it is below ground on all sides. If you have no basement, pick a small interior room. Use bathrooms, closets, or hallways.

Avoid top floors and rooms under the roof. Fallout settles on roofs and ground first. That increases radiation near those surfaces. Avoid rooms with many windows. Glass breaks and lets dust in.

If you must choose quickly, pick the nearest solid building. Do not waste time searching for the “perfect” place while outside.

Understand Fallout Timing: Why the First Hours Matter Most

Fallout drives many survival outcomes, so it is central to how to survive a nuclear attack. Fallout is dangerous because it can expose you to high radiation doses. The good news is that radiation levels drop fast. They can fall sharply within hours, then keep declining over days. This is why sheltering early and staying sheltered saves lives.

Fallout particles can be carried by wind. You might be far from the blast and still face fallout. You may not see it clearly. It can look like dust, ash, or sand-like grit. It can also be invisible. Do not rely on sight. Rely on timing and official alerts.

A practical rule: If you might be in the fallout path, get sheltered before fallout arrives. Near a target, fallout can start within 10–30 minutes. Farther away, it may take longer. Once fallout starts, going outside becomes risky. Every minute outdoors adds dose. If you must move, move early, move fast, and go indoors again quickly.

Do not “go pick up family” during early fallout unless it is truly life-or-death. You can reduce risk more by sheltering and coordinating later when radiation drops.

Decontamination: How to Remove Fallout From Your Body and Clothes

If you were outside after the blast, assume you have radioactive dust on you. You can remove most contamination with simple actions. Do it as soon as you get inside.

Step-by-step decon

- Take off outer clothing near the entry area. Do not shake it.

- Put clothes in a plastic bag. Tie or seal it.

- Keep the bag away from people and pets.

- Shower with lukewarm water and soap if available.

- Wash hair with shampoo, not conditioner. Conditioner can bind particles.

- If you cannot shower, wipe skin with a damp cloth. Focus on face, hands, neck, and hairline.

- Blow your nose gently. Rinse mouth. Wash hands again.

What not to do

- Do not scrub hard. Scrubbing can irritate skin and increase absorption.

- Do not use bleach on skin.

- Do not eat, drink, or smoke until you clean hands and face.

If you shelter with others, decon reduces indoor contamination. It keeps fallout dust from spreading onto floors, bedding, and food areas.

Improve Your Shelter With What You Already Have

You can boost shelter quality with common items. The goal is more mass between you and the outside. Focus on walls and ceiling that face outdoors, ground, or roof.

Quick upgrades

- Move to the lowest level you can access safely.

- Put bookcases, filled boxes, water containers, or furniture against outside-facing walls.

- Use mattresses, dense cushions, or folded blankets to add layers.

- If you have a basement, set up in a corner away from windows and outside doors.

- If you are in an apartment, choose a central hallway or interior room.

Water is useful because it adds mass. Fill bathtubs, sinks, and containers early if the water still runs. Stack filled containers near outside walls if it does not block exits.

Seal obvious gaps if fallout dust is heavy outside. Close windows. Shut vents if possible. Use towels at door bottoms. Do not make the space airtight if you use any flame device. You need safe ventilation. Focus on reducing dust entry, not sealing every crack.

Your shelter plan should still allow movement, toileting, and basic comfort. A “good enough” shelter you can stay in beats a perfect plan you cannot maintain.

Air, Dust, and Ventilation: Reduce Inhalation Risks Safely

Breathing in particles can increase risk, so air control supports nuclear attack. Your main defense is staying indoors. Fallout dust outdoors creates the highest risk. Indoors, keep air calmer and cleaner. Close windows and exterior doors. Turn off fans that pull outdoor air in, if you can. Avoid sweeping dry dust, because it re-suspends particles.

If you have masks, use them during decon or if you must go near entrances. Even a well-fitted cloth can reduce dust. A better option is a high-filtration mask if available. Still, masks do not replace shelter.

For ventilation, use common sense. If you have no power, your space will still exchange air slowly. That is fine. If you must run a generator, keep it outside and far from openings. Never run it indoors. Carbon monoxide kills fast.

If you have HVAC systems, you may be able to keep air circulating without drawing outdoor air. Settings vary. If you are unsure, shut it off during heavy fallout. Later, when radiation drops, you can ventilate briefly by opening an interior door to a less exposed side of the building. Keep it short and controlled.

Food and Water: What’s Safe, What to Avoid, and How to Store

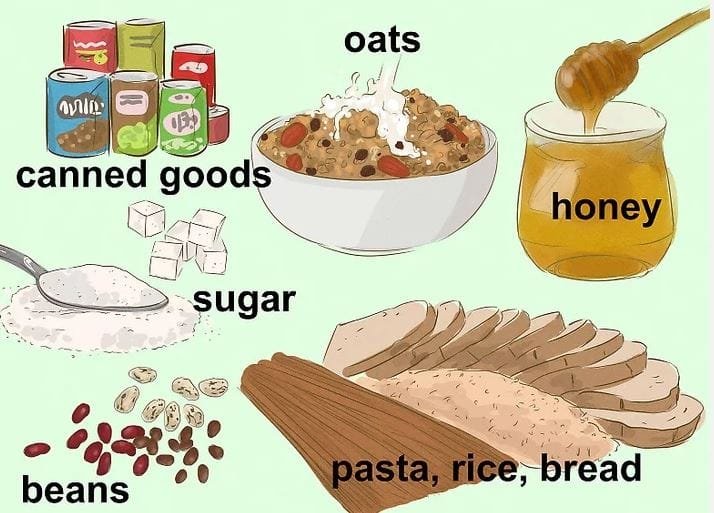

Food and water planning makes nuclear attack more realistic over several days. Most packaged food indoors is safe. The risk comes from open containers, outdoor produce, and water exposed to fallout dust. Prioritize sealed items.

Safer choices

- Canned food, sealed jars, and packaged snacks

- Food in closed cupboards or drawers

- Bottled water, sealed drinks, and stored water from before fallout

Higher-risk choices

- Food left uncovered outdoors or near open windows

- Fresh produce from outside during fallout

- Water from open containers exposed to dust

If tap water works early, fill containers and bathtubs. Label one container as “hand washing only” to protect drinking supplies. Use clean utensils. Wipe lids before opening. If dust may have entered, wipe surfaces with damp cloths. Put used cloths in a bag.

If you must use water of uncertain cleanliness, use filtration and disinfection methods when possible. Boiling helps with microbes, but it does not remove radiation. Avoid collecting rainwater or surface water during active fallout unless you have no alternative.

Eat smaller, regular meals. Hydrate steadily. Stress makes people forget water. Dehydration worsens fatigue and decision-making.

Communication and Information: Avoid Rumors, Use Reliable Signals

In a crisis, rumors spread faster than facts. You need reliable alerts and simple decision rules. Use battery radios if available. Keep phones on low power. Text often works when calls fail. Send short, clear messages.

Family communication plan

- Choose one out-of-area contact if possible.

- Use one simple status message: “Safe. Sheltering. Will update at 6 pm.”

- Avoid repeated calls that drain batteries and overload networks.

Pay attention to official guidance about shelter duration and safe movement routes. Authorities may identify fallout plumes, evacuation corridors, and medical support points. If you cannot access official updates, default to sheltering longer.

Limit exposure to panic content. Stress harms judgment. Assign one person to check updates at set times. Everyone else rests, eats, and maintains the shelter. If you hear something alarming, confirm it via at least two reliable sources before acting.

A calm, informed shelter group makes better choices. That can reduce unnecessary outdoor trips, accidents, and conflict during a long day indoors.

When to Move and When to Stay:

Movement can save lives in special cases, but it can also raise radiation dose. This is why decision-making is part of nuclear attack. Use this simple table.

Situation |

Best action |

Why |

|

You are outdoors and fallout has not started |

Get inside immediately | You can beat fallout timing |

|

Fallout is falling or likely soon |

Stay indoors | Outdoor dose rises fast |

|

Your shelter is on fire or collapsing |

Move to nearest safer building fast | Immediate hazards override |

| You are in a car near a solid building | Park and enter the building |

Car shields poorly |

| You have a basement available | Shelter there |

Earth blocks radiation well |

| Authorities order evacuation with a route | Follow when advised and safe |

They may route around plumes |

If you must move, cover skin, wear a mask if you have one, and minimize time outside. Move with purpose. Do not wander. Once inside, decontaminate again.

If you are already in a good shelter, the best move is often no move. Many people want action because waiting feels scary. In fallout conditions, patience is protection.

First 24 Hours: Shelter Routine That Reduces Risk and Stress

The first day can feel long. A routine improves a nuclear attack by reducing mistakes. Create a simple schedule: decontamination check, water plan, food plan, and rest. Keep everyone away from entrances after initial decon. Set one “dirty zone” near the door for shoes, bags, and outer layers. Keep a “clean zone” where you eat and sleep.

Basic day-one routine

- Hour 0–2: Get sheltered, decon, secure doors and windows

- Hour 2–6: Improve shielding, fill water, prepare sanitation setup

- Hour 6–12: Rest in shifts, check updates at set intervals

- Hour 12–24: Eat, hydrate, manage stress, keep children calm

For sanitation, use lined buckets or a toilet with limited flushing if water is scarce. Seal waste bags tightly. Store them away from living space. Wash hands often using a small amount of water and soap.

Keep warm. Cold stress increases fatigue. Use blankets and layers. Avoid candles if possible because of fire risk. Use flashlights. If you must use flames, keep them stable, supervised, and away from paper and bedding.

Small, steady actions beat panic decisions.

Medical Basics: Burns, Cuts, Shock, and Radiation Concerns

Medical care may be delayed. Treat immediate injuries first. Control bleeding with pressure. Clean wounds with clean water if available. Cover with clean cloth or bandage. For burns, cool with clean, cool water for several minutes if you can. Cover with a clean, non-stick dressing. Do not apply butter or oils.

Watch for shock. Signs include pale skin, weakness, confusion, and rapid breathing. Keep the person warm and lying down. Reassure them. Give small sips of water if they are conscious and not vomiting.

Radiation exposure symptoms can include nausea and vomiting, but stress can cause the same. Do not assume symptoms equal radiation. Focus on what you can control: reduce exposure, decon, hydrate, and rest. If someone vomits repeatedly, becomes confused, or has severe burns, seek medical help when authorities provide safe routes.

Keep a list of medications and conditions. If you have essential medicines, ration carefully but do not stop critical drugs without medical advice. For asthma, heart disease, or diabetes, stable routines and hydration matter.

Your shelter group can also support mental health. Calm words, simple tasks, and rest reduce panic.

Children, Older Adults, and Pets: Extra Steps That Matter

Planning for children, older adults (such as people over 65 or 70), and pets is an essential part of understanding a nuclear attack. These groups often have different physical, emotional, and medical needs, which require thoughtful preparation and calm support during sheltering.

Children may feel confused or frightened by loud sounds, darkness, or sudden changes. Keep them close and explain what is happening in simple, reassuring language. Giving children small tasks, such as organizing supplies or handing out water, helps them feel useful and reduces anxiety. Maintain routines where possible, including rest times and meals.

Older adults may need extra attention for hydration, warmth, mobility, and medication schedules. Stress and disruption can worsen existing health conditions, so clear communication and gentle pacing are important. Ensure walking paths are clear to prevent falls, and keep essential medications easily accessible.

Pets can carry radioactive dust on their fur if they were outdoors. Wipe pets with a damp cloth, clean paws carefully, and keep them indoors. Store pet food safely and prevent animals from drinking contaminated water.

Including everyone in your shelter plan reduces risk, prevents panic, and improves overall safety for all occupants.

Supply List That Matters Most: “Short and Strong” Essentials

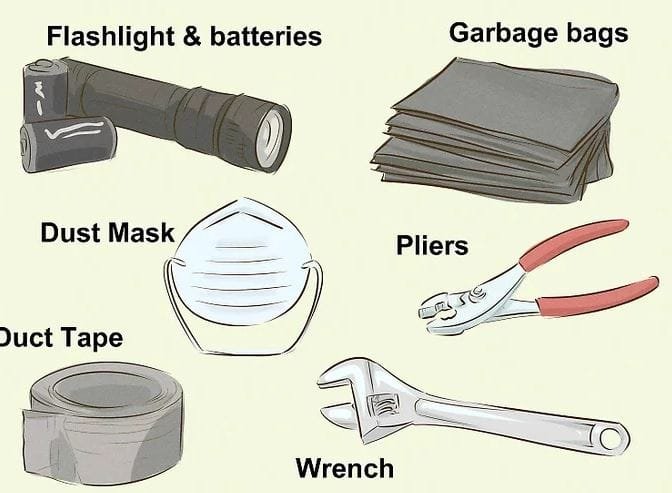

You do not need a giant bunker to learn how to survive a nuclear attack. A short list covers most needs for a few days. Focus on water, food, light, hygiene, and information.

Essentials

- Water: bottles, jugs, or filled containers

- Food: canned and packaged items, manual can opener

- Light: flashlights, spare batteries

- Information: battery radio if available

- Hygiene: soap, wipes, trash bags, gloves

- First aid: bandages, antiseptic, basic meds

- Warmth: blankets, extra clothes

- Power: phone power bank if you have one

- Tools: duct tape, scissors, marker, zip bags

Optional but useful

- Masks for dust

- Plastic sheeting for a simple “dirty zone”

- Water purification tablets (for microbes, not radiation)

- Games or books to keep calm

Store supplies in one accessible place. If an alert happens, you can grab them fast. If you cannot prepare now, still remember the priorities. A solid building, interior shelter, and clean body reduce risk more than fancy gear.

Common Mistakes to Avoid During Fallout Sheltering

Mistakes can undo good sheltering. Avoiding them strengthens how to survive a nuclear attack. The most common mistake is leaving too soon. People feel trapped and try to drive away. That puts them outside during the most intense fallout period. Another mistake is sheltering in the wrong spot. Rooms with windows and rooftops increase exposure.

Avoid these errors:

- Standing near windows after a flash

- Going outside to “check” conditions

- Shaking dusty clothing indoors

- Eating with unwashed hands

- Letting pets track dust inside

- Using generators indoors

- Lighting many candles and creating fire risk

- Spreading rumors and making rushed decisions

Also avoid “all-or-nothing” thinking. You do not need perfect information to take safe steps. Get inside. Get to the center and lower levels. Clean up. Stay sheltered.

If you must go outside later for a critical reason, do it with planning. Cover skin. Move quickly. Decon again. Keep trips short and rare.

Good survival often looks boring. It looks like waiting, drinking water, and staying calm.

After 48 Hours to One Week: Safer Outdoor Steps and Recovery Planning

As time passes, radiation drops. This is still part of how to survive a nuclear attack, because recovery needs smart timing. Follow official guidance first. If you must act without it, use caution. Limit outdoor time. Choose short, necessary trips only. Wear long sleeves, pants, closed shoes, gloves, and a mask if you have one. Avoid kicking up dust.

Do outdoor tasks in this order:

- Check for structural hazards and fire risks near your shelter.

- Collect critical items only if you can do it fast.

- Return and decontaminate: remove outer layers, bag them, wash exposed skin.

Do not eat outdoor garden produce until authorities say it is safe. Do not drink from open sources. Use stored food. Keep using sealed items. If you need to relocate, wait for official routes. They may direct you around hotspots and toward assistance.

Recovery also means documentation. Write down injuries, medication use, and supply status. Coordinate with neighbors if safe. Share information, not rumors. Help with child care, water sharing, and first aid skills.

A steady approach turns a frightening event into manageable steps.

Faqs About Nuclear Attack

How long should I stay in shelter after a nuclear attack?

Stay sheltered as long as officials advise. If you have no updates, shelter longer rather than leaving early.

Is a basement always the best option?

Often yes, because earth blocks radiation well. If no basement exists, use an interior room away from outer walls.

Should I evacuate immediately if I’m far from the blast?

Not during early fallout risk. Get inside first. Move later only if your shelter is unsafe or officials direct you.

Can I wash off fallout with water only?

Soap and water work best. If you lack a shower, use damp wipes and change clothes without shaking them.

Does tap water become unsafe right away?

Not always. Fill containers early if water works. Use official guidance when available and avoid open outdoor water sources.

Wrap-Up

Survival in a nuclear emergency is not about bravery. It is about timing and basics. How to survive a nuclear attack starts with one fast decision: get inside and get away from windows. Then you win the next hours by staying deep in the building, adding shielding, and keeping fallout dust off your body and out of your living space.

You win the next few days by drinking clean water, eating sealed food, and avoiding unnecessary outdoor trips. The situation may feel unreal, but your actions can stay simple and controlled. Make your shelter calm.

Create small routines. Check reliable updates at set times. Help children and elders feel safe through structure. If you remember only one line, remember this: Inside, below, center—then stay put. That single habit can shift your odds more than any expensive equipment.