How Nuclear Bomb Works? At its core, it uses nuclear reactions that release an extreme amount of energy in a very short time. That energy comes from changes inside atomic nuclei, not from chemical burning like gasoline or TNT. A nuclear weapon forces atoms to split (fission) or combines light atoms (fusion) so quickly that the energy release becomes explosive. The physics behind this sits in basic nuclear science, but the real-world consequences reach far beyond science into history, politics, and human safety.

This article explains the process in a clear, educational way. It focuses on the principles: what fuels the energy, how chain reactions grow, what happens in the first milliseconds, and why blast, heat, radiation, and fallout occur. It also explains thermonuclear weapons at a high level, along with effects like electromagnetic pulse (EMP). You will learn key terms such as criticality, prompt radiation, and fallout patterns, without entering into engineering instructions or construction details.

By the end, you will understand what makes nuclear explosions different from conventional explosions, why the damage spreads so widely, and how the world tries to prevent nuclear war through controls and treaties. The goal is simple: make the science understandable while respecting safety and responsibility.

The Big Idea: Nuclear Energy vs Chemical Energy

To understand How Nuclear Bomb Works? start with the difference between nuclear energy and chemical energy. Chemical explosives rearrange electrons around atoms. They break and form chemical bonds. Even the strongest chemical explosives release energy measured in megajoules per kilogram. Nuclear reactions change the nucleus itself. They alter the identity and structure of atoms. That releases energy measured in terajoules per kilogram, which is millions of times higher per unit mass.

This gap explains why a relatively small nuclear device can equal the explosive force of many thousands of tons of TNT. In chemical reactions, mass stays essentially the same, and energy comes from bond differences. In nuclear reactions, a tiny fraction of mass converts into energy. Einstein’s relation, E = mc², describes this conversion. The “c²” term is huge because c is the speed of light. So even a small mass difference becomes an enormous energy output.

Nuclear weapons rely on extremely fast reaction rates. The reactions must multiply and release energy before the system can expand and cool. If the reaction stays slow, it becomes a controlled process like in a nuclear reactor. If it runs away in microseconds, it becomes an explosion.

So the big idea is not “more fuel.” The big idea is “a different kind of fuel,” where the nucleus provides the energy source, and the reaction grows at a pace that overwhelms any natural stabilizing effect.

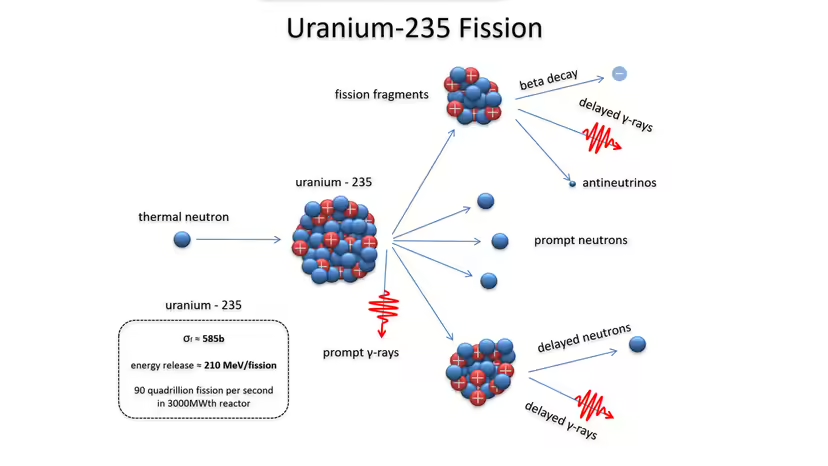

Atoms, Nuclei, and Why Some Nuclei Split

Atoms contain a nucleus made of protons and neutrons. Protons carry positive charge, so they repel each other. The strong nuclear force holds them together at extremely short distances. Stable nuclei keep a balance between these forces. Unstable heavy nuclei struggle to stay intact. They can split into smaller nuclei, which often fit into more stable arrangements.

When certain heavy nuclei split, they release energy in three main forms:

- Kinetic energy of fragments (the split pieces fly apart fast)

- Neutrons (free neutrons get ejected)

- Gamma rays (high-energy electromagnetic radiation)

The release happens because the total binding energy of the final products becomes greater than that of the original nucleus. The “difference” appears as released energy.

This matters because those released neutrons can trigger more splits in nearby nuclei. That creates a multiplying process called a chain reaction. If each split causes, on average, more than one additional split, the reaction grows exponentially. If each split causes less than one additional split, it fades.

In simple terms, nuclear weapons depend on a short window where splitting multiplies faster than the system can fly apart. That timing decides whether the outcome becomes a massive explosion or a much smaller release. The nucleus does not “burn.” It transforms and releases energy through fundamental forces.

Nuclear Fission: The Chain Reaction Explained

Most “atomic bombs” use fission, which means splitting heavy nuclei. The chain reaction is the heart of the process. Here is the concept:

- A neutron hits a heavy nucleus.

- The nucleus becomes unstable and splits.

- The split releases energy plus extra neutrons.

- Those neutrons hit other nuclei and repeat the process.

This becomes explosive only when the reaction turns supercritical, meaning each generation of fission produces more fissions than the previous generation. The growth can become extremely fast because each generation happens in a tiny fraction of a second.

Three factors strongly influence whether the chain reaction grows:

- Amount of fissile material: More material provides more targets.

- Geometry and density: A compact shape increases neutron collisions.

- Neutron losses: Neutrons can escape or get absorbed without causing fission.

A nuclear reactor also uses fission, but it stays controlled. It uses moderators, control rods, and design features to keep the reaction near steady. A weapon forces a rapid, uncontrolled rise. The energy release occurs in a very short time, so the material heats, expands, and tears itself apart. That expansion quickly ends the reaction, but by then the energy already rushed out.

So when people ask How Nuclear Bomb Works?, the core answer is: it drives fission into a runaway chain reaction before the material can expand enough to stop it.

Criticality: Subcritical, Critical, and Supercritical

Criticality describes the “growth behavior” of a chain reaction.

- Subcritical: The reaction dies out. Too many neutrons escape or get absorbed.

- Critical: The reaction sustains itself at a steady rate. One fission leads to about one more.

- Supercritical: The reaction grows. One fission leads to more than one more on average.

Weapons depend on a rapid move into a supercritical state. The system must remain supercritical long enough to produce a huge number of fissions. That time window is short because the energy release causes rapid heating and expansion. Expansion lowers density, increases neutron escape, and pushes the system back toward subcritical. In other words, the explosion destroys the conditions that created it.

Two key terms often appear:

- Prompt neutrons: Neutrons released immediately during fission.

- Delayed neutrons: A small fraction released later from fission products.

Reactors rely on delayed neutrons for controllability. Weapons depend mainly on prompt behavior because the time scale is too fast for delayed processes to matter.

When you hear “critical mass,” think of it as a simplified concept. Real criticality depends on shape, density, surrounding materials, and neutron behavior. The important point remains: the reaction must multiply fast, and the system must stay intact long enough for that multiplication to release enormous energy.

How the Energy Becomes an Explosion

A nuclear explosion is not just “energy release.” It is how that energy couples into the surrounding environment. In the first instants, fission fragments slam into nearby atoms. They transfer kinetic energy as heat. Temperatures rise to extreme levels. That creates a rapidly expanding, superheated gas and plasma. The expansion produces a shock wave.

Here is the key conversion chain:

- Nuclear reactions release energy inside nuclei.

- Energy becomes heat and radiation almost instantly.

- Heat creates high pressure.

- High pressure drives a shock wave outward.

- The shock wave causes blast damage.

Unlike conventional explosives, nuclear detonations also produce intense thermal radiation (light and heat) and ionizing radiation. The thermal flash can ignite fires over wide areas. Ionizing radiation can cause biological damage near the detonation, and fallout can spread hazards downwind.

Another difference is speed. Chemical explosions depend on how fast a chemical reaction front moves. Nuclear reactions occur on far shorter time scales, so the power output becomes enormous. Power means energy per unit time. Even if a conventional explosive released similar energy (it cannot), it would need to do so in the same short time to match the shock effect.

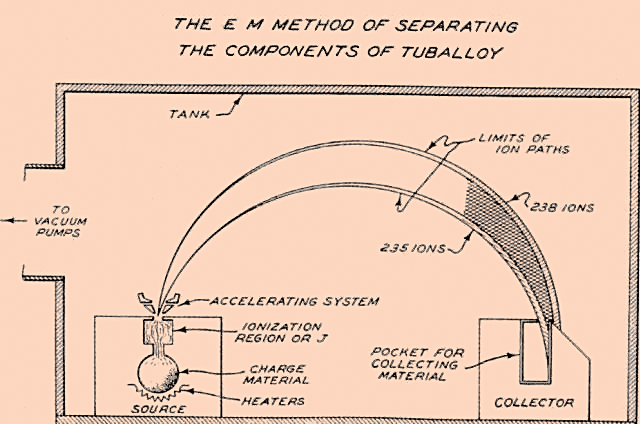

Fission Weapon Types

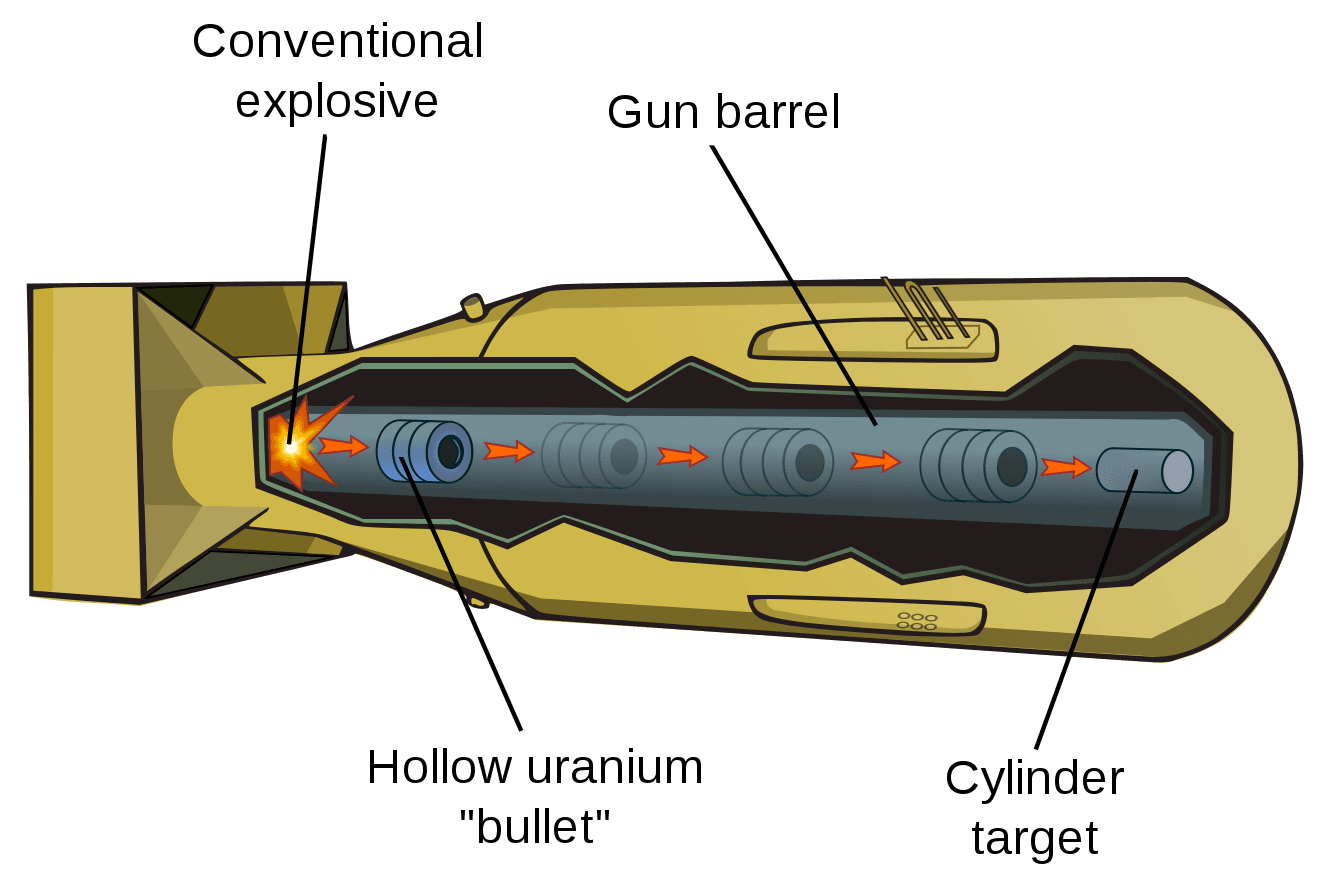

People often ask for “types” when learning How Nuclear Bomb Works? At a broad, non-technical level, fission weapons have used different approaches to reach a supercritical state quickly. The details matter for engineering, but the principle stays consistent: increase the effective reactivity fast, then let the chain reaction run for milliseconds.

Common high-level categories include:

- Assembly-type concepts: Rapidly bring fissile material into a more reactive configuration.

- Compression-type concepts: Increase density to reduce neutron escape and increase collision rates.

Both aim to reduce neutron losses and boost multiplication. Designers also consider timing because if the configuration forms too slowly, the reaction may begin early and reduce yield. If it forms quickly and holds briefly, the reaction can grow much larger.

This article avoids construction instructions. Still, understanding the conceptual goal helps: the weapon briefly creates conditions where neutrons cause many successive fissions before the system expands. That short-lived supercritical phase drives the explosive release.

A useful mental model is a “race”:

- The chain reaction tries to multiply as fast as possible.

- Expansion tries to end the reaction by lowering density.

The explosion’s scale depends on which process dominates for those few instants. That is the core logic behind fission weapon behavior at a conceptual level.

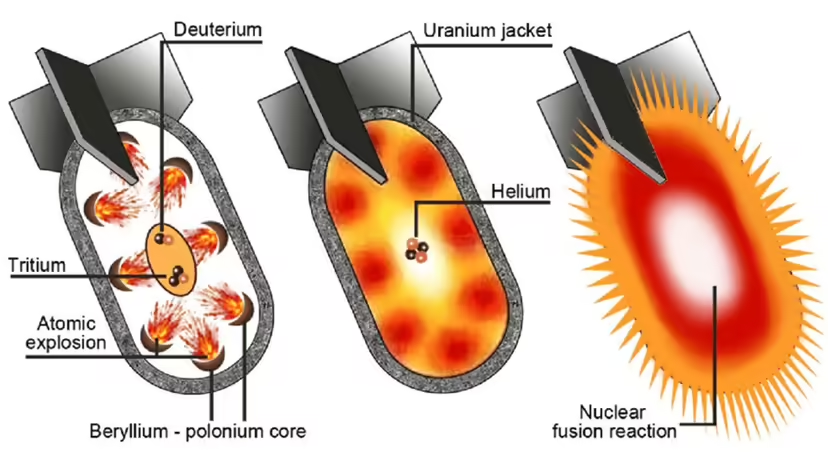

Thermonuclear (Fusion) Weapons: The Big Picture

Some nuclear weapons are thermonuclear, often called hydrogen bombs. They involve fusion, where light nuclei combine into heavier nuclei and release energy. Fusion powers the Sun, but the Sun uses gravity and huge mass. A weapon uses extreme temperature and pressure for a very short time.

Fusion itself releases enormous energy, but it has a challenge: it needs very high conditions to start. In weapon history, a fission explosion has served as the trigger source of those extreme conditions. Once fusion begins, it can add a large fraction of total yield.

At a conceptual level, thermonuclear weapons involve:

- A stage that creates intense heat and radiation quickly.

- A stage where fusion reactions occur in that extreme environment.

- Additional nuclear interactions that can increase energy output and affect fallout.

Fusion reactions produce very energetic particles that heat the plasma further. That supports more fusion while conditions remain extreme. However, like fission, the process ends as the system expands and cools. Time remains the controlling factor.

Thermonuclear weapons can reach much higher yields than basic fission devices. They also raise broader humanitarian and environmental risks because larger yields can produce larger blast zones and wider contamination risks depending on conditions.

What Happens in the First Milliseconds

The early timeline of a nuclear detonation explains why effects arrive in waves.

Within microseconds to milliseconds:

- Nuclear reactions release energy.

- The immediate region becomes extremely hot.

- A fireball forms and expands rapidly.

Thermal flash:

- Intense light and heat radiate outward.

- The flash can cause burns and ignite materials at distance.

Shock wave formation:

- Expansion compresses air into a high-pressure front.

- That front travels outward as a blast wave.

Prompt radiation (near the burst):

- Gamma rays and neutrons can reach people and materials near the detonation.

- This happens quickly and decreases with distance.

As the fireball rises, it pulls dust and debris. In surface or near-surface detonations, that debris can become radioactive and later fall as fallout. In high-altitude bursts, fallout may be less local, but other effects like EMP can increase.

The sequence matters for survival and response. Blast arrives after the flash because light travels faster than sound and shock. People may see the flash before they feel the blast. That timing has shaped many historical descriptions.

This timeline also shows why nuclear effects are multi-dimensional. A conventional blast mainly causes pressure damage. A nuclear burst combines pressure, heat, and radiation in a complex pattern that depends on altitude, weather, terrain, and yield.

Blast Effects: Pressure, Wind, and Structural Damage

Blast damage comes from rapid pressure changes and extreme winds. The blast wave includes a sharp rise in pressure, followed by a drop and a powerful flow of air. Buildings fail when pressure exceeds design limits, when windows shatter, or when walls and roofs collapse.

Key blast factors include:

- Peak overpressure: The maximum pressure above normal atmosphere.

- Dynamic pressure: The force from high-speed winds behind the shock front.

- Duration: How long the pressure remains elevated.

Nuclear explosions can produce a longer-duration blast wave than many conventional explosives at similar peak pressures. That increased impulse can worsen structural damage.

Common outcomes include:

- Shattered glass over wide areas, causing injuries.

- Collapse of weak structures near the center.

- Severe damage to roofs, doors, and frames at moderate distances.

- Debris becoming high-speed projectiles.

Urban environments can amplify effects. Shock waves reflect off buildings and create complex pressure patterns in streets. Terrain and altitude also influence the blast spread.

Emergency planning often focuses on blast zones because they define immediate destruction and injury patterns. However, blasting is only one part of the total hazard picture. In nuclear detonations, fire and radiation can increase casualties even beyond the areas of severe structural collapse.

Thermal Radiation: The Flash, Burns, and Firestorms

Thermal radiation includes visible, infrared, and some ultraviolet energy emitted by the fireball. It can cause:

- Skin burns (from direct exposure)

- Eye injuries (including flash blindness)

- Ignitions (starting fires in flammable materials)

The thermal flash can ignite paper, fabric, dry vegetation, and certain building materials. Many small fires can merge into larger fires. In dense urban areas, the combination of many ignitions plus damaged water lines can make firefighting difficult.

In some scenarios, large fires can create strong inflows of air, which feed flames and increase temperatures. People often use the term “firestorm” for intense, sustained urban fires that generate their own winds. Firestorms depend on many conditions, including fuel load, weather, and urban density.

Thermal effects depend strongly on:

- Distance

- Line of sight (hills and buildings can block exposure)

- Atmospheric clarity (dust and clouds can reduce intensity)

- Burst altitude (which changes how heat spreads)

Thermal radiation often causes damage beyond zones of heavy blast damage. That is why Nuclear Bomb detonations can produce widespread burns and city-scale fires. This aspect makes nuclear weapons uniquely devastating.

Ionizing Radiation: Prompt Effects and Radiation Sickness

Ionizing radiation can remove electrons from atoms and damage biological tissue. Nuclear detonations produce radiation in two main ways:

- Prompt radiation: Emitted immediately at detonation.

- Residual radiation: From radioactive fallout and activated materials afterward.

Prompt radiation includes gamma rays and neutrons. It decreases rapidly with distance and shielding. In general, prompt radiation poses the highest risk closer to the burst, especially when blast does not immediately kill or incapacitate.

Biological impact depends on dose and exposure time. High doses can cause acute radiation syndrome, which may involve nausea, vomiting, immune suppression, bleeding, and organ failure. Lower doses can increase long-term cancer risk.

Neutrons can also activate materials they strike, turning some into radioactive isotopes. This can add to residual hazards depending on burst conditions.

Shielding matters. Dense materials reduce gamma exposure. Distance also matters greatly because radiation intensity drops quickly as it spreads outward. In real events, building materials, terrain, and protective structures can change exposure patterns dramatically.

Radiation risk can persist in contaminated areas. Fallout particles can settle on soil, roofs, and surfaces. People can face exposure from external contact, inhalation, or ingestion if water and food become contaminated.

Radiation is often the most feared effect because it is invisible. Understanding it clearly helps separate myths from reality and supports informed thinking about nuclear risks.

Fallout: Why It Happens and How It Spreads

Fallout refers to radioactive particles that return to the ground after a nuclear explosion. It becomes especially significant when the detonation occurs at or near the surface. The fireball can pick up soil, building material, and debris. Neutron activation and fission products can attach to that debris. The rising column carries it upward, and winds transport it downwind.

Fallout patterns depend on:

- Wind speed and direction at multiple altitudes

- Burst height (surface bursts produce more local fallout)

- Weather (rain can bring particles down faster)

- Particle size (larger particles fall sooner; finer particles travel farther)

Fallout can create “hot spots,” where deposition becomes heavier. Rainfall can concentrate contamination in streaks or patches. That makes real-world hazards uneven.

The danger of fallout changes over time because many isotopes decay. Radiation levels often drop significantly in the first hours and days, though some contaminants can persist longer. Because fallout is time-dependent, response strategies often emphasize rapid sheltering, avoiding contaminated dust, and controlled evacuation when safe routes exist.

Fallout also affects agriculture, water supplies, and long-term habitability. Contaminated soils can require remediation, restrictions, or long recovery periods.

Fallout is a key reason nuclear weapons create long-lasting consequences beyond immediate blast and fire. It also explains why burst conditions matter so much when discussing overall harm.

EMP: The Invisible Shock to Electronics

An electromagnetic pulse (EMP) is a burst of electromagnetic energy that can disrupt or damage electronics. EMP becomes a major concern in high-altitude nuclear detonations. At high altitude, gamma rays interact with the upper atmosphere. This interaction can produce fast-moving electrons and electromagnetic disturbances that propagate over large regions.

EMP can affect:

- Power grids and transformers

- Communication networks

- Computers and industrial control systems

- Radio systems and navigation tools

The impact depends on many variables, including the burst altitude, device characteristics, and the resilience of infrastructure. Modern societies depend on electronics for healthcare, transport, water supply, finance, and emergency response. So even without direct blast damage, EMP-related disruption could cause severe secondary crises.

EMP effects often get exaggerated in fiction, but they remain a real technical concern in strategic planning. Engineers can harden systems with shielding, surge protection, redundancy, and careful grounding design. Some critical infrastructure uses protection measures, but coverage varies widely.

EMP adds another layer to How Nuclear Bomb Works? because it shows that nuclear detonations can harm systems at a distance without physical contact. That makes nuclear risk not only about immediate destruction, but also about cascading failures across interconnected technology.

Nuclear vs Conventional Explosions

|

Feature |

Conventional Explosives | Nuclear (Fission/Fusion) |

|

Energy source |

Chemical bonds |

Nuclear reactions in the nucleus |

|

Energy density |

Much lower | Extremely high |

|

Main damage mechanism |

Blast and fragments | Blast + thermal + radiation + fallout |

|

Duration of release |

Slower than nuclear scales |

Very rapid, huge power output |

| Radiation hazard | Minimal |

Major (prompt + residual) |

| Long-term contamination | Rare |

Possible, especially with fallout |

| Infrastructure effects | Localized |

Can be regional, plus EMP risk |

A conventional explosion produces a shock wave and heat, but it does not produce large amounts of ionizing radiation or radioactive debris. Nuclear detonations combine multiple hazards at once. That combination makes planning and response harder.

Also, Nuclear Bomb detonations can cause widespread fires and medical crises because many injuries happen simultaneously. Burns, trauma, and radiation exposure can overlap. Hospitals and emergency services can become overwhelmed, especially if transport networks fail.

This table does not mean one hazard “matters more” than another. It shows how Nuclear Bomb events stack hazards together. That stacking drives the catastrophic reputation of nuclear weapons.

Common Myths and Clear Facts

Many misunderstandings appear when people discuss How Nuclear Bomb Works? Let’s correct a few common myths.

Myth 1: A Nuclear Bomb keeps exploding forever.

Fact: The nuclear reaction ends quickly because the device expands and becomes less reactive.

Myth 2: Any radiation exposure means certain death.

Fact: Risk depends on dose, time, distance, and shielding. Many exposures cause increased risk, not immediate death.

Myth 3: Fallout spreads evenly like a blanket.

Fact: Fallout forms patterns. Wind and rain create streaks and hot spots.

Myth 4: Nuclear winter is guaranteed after any nuclear use.

Fact: Scientists debate severity based on scale, targets, and fire soot injection. Large-scale war raises concern, but outcomes vary by scenario.

Myth 5: A nuclear blast is only “a bigger bomb.”

Fact: Nuclear Bomb effects include thermal flash, prompt radiation, fallout, and possible EMP. These change the disaster profile.

Clear thinking matters because panic and misinformation can worsen crises. Preparedness depends on realistic understanding. Education helps people grasp the science and also the limits of what is knowable in a complex real-world event.

Myths often grow because nuclear topics feel secretive and frightening. The best antidote is an accurate, responsible explanation that sticks to principles and impacts.

Faqs About Nuclear Bomb

How Nuclear Bomb Works?

It triggers extremely fast nuclear reactions that release huge energy as blast, heat, and radiation.

What is the difference between fission and fusion weapons?

Fission splits heavy nuclei; fusion combines light nuclei. Fusion designs can reach far higher yields.

Why is fallout worse in surface detonations?

The fireball pulls debris into the cloud, and radioactive particles fall back downwind.

Can a nuclear explosion damage electronics far away?

Yes, a high-altitude burst can create EMP that disrupts power and communications over wide areas.

Is nuclear radiation always fatal?

No. Health outcomes depend on dose, shielding, time, and medical care, though high doses are dangerous.

Wrap-Up

When you ask How Nuclear Bomb Works?, the most important takeaway is not a single “trick” or part. It is the combination of runaway nuclear reactions and their layered effects.

In a blink of time, nuclear energy turns into a fireball, a crushing shock wave, intense heat, and ionizing radiation. Then, depending on conditions, fallout and EMP can extend the crisis far beyond the blast zone.

That is why nuclear weapons reshape everything: cities, health systems, environment, and global stability.

Understanding science does not glamorize it. It clarifies why the risk remains so serious and why prevention matters worldwide. Knowledge replaces rumors with reality, and reality shows the same truth every time: nuclear explosions change lives in seconds and can echo for decades.